To the Unsung Heroes of Pollination

As part of our lead up to Pollinator Day this Saturday,

Weird Animal Wednesday has spotlighted a particular pollinator species from the

butterfly, moth, bee, bat, and bird families – our salute to the important work

these creatures do in keeping countless species of plants from becoming extinct.

We have one more Wednesday left before 6/21. What other pollinator types remain

unnamed? Several, it turns out.

In 2006, the

U.S. Senate created a National Pollinator Week to

“recognize the importance of pollinators to ecosystem health and agriculture in

the United States.” So, we’d be remiss if we failed to acknowledge these

lesser-known pollinators. The heretofore unmentioned heroes of pollination

include many types of flies, wasps, and beetles. And some would also add the

ant. OK, it’s a big tent, or more precisely, a big plant kingdom. And these

little creatures are the unsung pollinator heroes of that world. In some cases

their pollination is an essential, not just an incidental benefit.

Let’s review some aspects of the pollination “relationship”.

First of all, it is a relationship. Except

in the case of self-pollination or wind pollination, two different

representatives, each from distinct biological kingdoms, are involved. What

brings this “odd couple” together? One motivational factor is reciprocal

benefit. The flower attracts a pollinator using several means at its disposal: color

and accessibility (for instance, shape), scent in some cases, and nutrition

(nectar, and possibly pollen or wax) or subterfuge.

Nutrition or subterfuge. Well, nutrition is straightforward;

almost all of our better-known pollinators – bees, butterflies, moths, bats,

and birds – derive nutritional benefits. Most of the lesser-known animals –

flies, wasps, and beetles – also utilize plant nectar for energy. But some

plants are deceptive, promising what they don’t deliver. For instance, some

orchid species imitate female wasps. The male attempts (unsuccessfully) to

“mate” with the orchid; the orchid receives a pollination benefit. Pollination

is about sex, after all – and sometimes it’s not confined to plant sex, even if

the insect sex is just a fantasy. This is a case where the benefits are not

exactly reciprocal, but hope springs eternal, so it’s a “sure thing” to the

orchids’ benefit that these male wasps will get fooled again.

Sometimes the subterfuge involves a promise of a meal the

plant can’t deliver. But the insect doesn’t know it. Many flies and beetles are

“adventurous diners”, and plants that specialize in attracting these species

don’t just rely on their good looks and nectar sources; they also beckon

beneficial insects by mimicking the rotten meat these insects consume. A

suitably stinky aroma combined with a color the shade of decomposing flesh is a

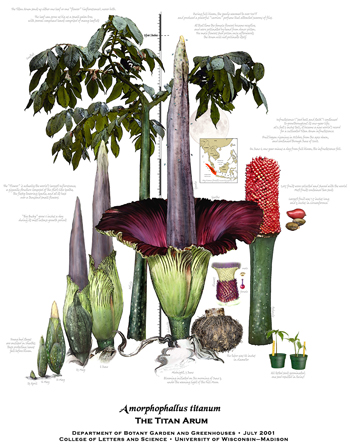

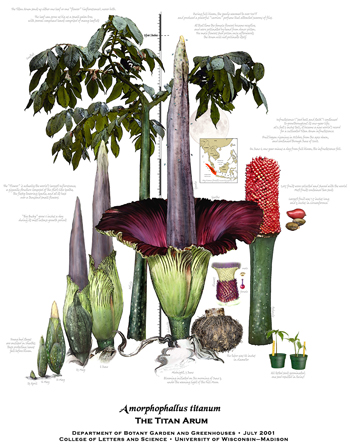

powerful attractant. The mammoth Titum

arum, affectionately known as the Corpse Flower, is a huge case in point. Its

6-8 foot inflorescence is short-lived, but makes a powerful putrid statement. The

first night is when the female flowers are open for business, the tall central

spadix actually heats up to 98 degrees Fahrenheit, just below normal living

human body temperature – the better to disburse it’s scent to passing flies

that, hopefully, have just finished a visit to another Corpse Flower and have a

little of its pollen to dispense. To the human eye it is a repulsive shade of

purple-brown/maroon, and phosphorescent green. When one bloomed in 2005 at the

National Arboretum, the building stayed open into the wee hours to accommodate

the flood of (human) visitors wishing to witness a floral rarity. Unfortunately,

the Titum arum chose to bloom just before Christmas in Washington, DC. It is

unlikely any of its visitors included flies that had recently paid call to

another blooming member of its species.

If the insect is sometimes the loser in the pollination

relationship, the plant can also lose. Consider the wasp. Some species, like

the great black wasp is a straightforward pollinator. Others, like the bee wolf

wasp linger on the flowers that its prey visits; its meal consists of the

pollinator, and any pollination that occurs because of the encounter is

strictly random. But some species are truly the black sheep of the plant-insect

relationship. Take the western yellowjacket. It’s an outright nectar thief,

robbing the plant of its biggest asset while providing no pollination services

at all. It accesses the nectar by boring a hole in the flower; and that hole

can be used by opportunistic ants or flies that would otherwise not be able to

gain entry. A true scientist shouldn’t judge, but the rest of us can say,

“Shame, shame.”

A clarification of the word “relationship” is also in order.

When we said,”two different representatives, each from distinct biological

kingdoms are involved,” the numerical reference to “two” was only a

generalization. In truth, most flowers can be pollinated by a range of animals.

And most pollinators can access many flowers. In the case of pollinating wasps,

bees, and beetles, which lack the long proboscis of other animals, the ideal

flower shape is relatively open or shallow, with easily accessible pistils. But

that too is a general not an iron-clad rule. And then, there is the “perfect

match,” where animal and plant pair is so specialized that no other creature

can partake of the union. The fig wasp that pollinates only the fig, which in

turn produces enough seeds to feed the wasp and to perpetuate itself, forms a

mutually obligate pair. Or the yucca month. Such tight relationships are of

necessity mutually beneficial. And perilous. For if either the pollinator or

the plant dies, survival of the obligate partner is nil. Unless, in the case of

the vanilla orchid, a human intervenes and pollinates the plant. Vanilla is

such a prized spice that humans will go to these length. Last, but not least,

timing is everything. Pollen and pollinator must be in the right place at the

right time, or all is for naught.

If you are a robotics aficionado, perhaps you’re envisioning

a world where pollination services for our “favored plant species” could be

performed by drones. We have produced micro-drones. The problem is, we still

don’t know enough about how many of our key plant species are pollinated. And

we can’t just worry about pollinating OUR favorites while forgetting the unsung

heroes of the plant world that keep our world healthy. What we do know is that

countless pollinators are losing essential habitat. You don’t have to be a

rocket (or robotics) scientist to be able to help keep these natural

relationships going. Devote a small piece of your property to a natural

pollinator sanctuary. If your neighbor does the same, you’ll have a chain of

oases for creatures trying to survive an urban/suburban dessert.

So let’s celebrate our pollinators! Join us at the GTM on

6/21 for

Pollinator Day. And keep the celebration (and the

pollinators) going. See the Native Plant Wildlife site for creating a

pollinator oasis in celebration of

National Pollinator Week. And learn more about

Creating a Natural Habitat for our Florida native pollinators.

Additional Links